Essential History: Compact Living

With the Compact Living collection, FRAMA turns its attention to the case studies in architecture and interior history where limited space has served as an opportunity—rather than a drawback.

For some of the most revered names in architecture, impactful designs came from projects with limited space and resources. Today, this can serve as a reminder and inspiration to those living in city apartments, shared spaces, small houses, or remote cabins that arranging a space to suit its particular size can lead to some of the most interesting design innovations. From Charlotte Perriand to Eileen Gray, Le Corbusier to Charles Gwathmey, Alvar and Elissa Aalto to Charles and Ray Eames, small scale has rarely resulted in small ideas.

Charlotte Perriand's Studio Apartment, Place Saint-Sulpice, 1927

© Une vie de création, Édition Odile Jacob, Paris, 1998In 1927, Charlotte Perriand began her career (at only 24 years old) with the redesign of her own apartment in Saint-Sulpice in Paris—using industrial materials like aluminum, glass, and steel to take a modern approach with clean lines and a minimal aesthetic. Embracing functionalism and adaptability, she designed furniture specifically for small spaces including folding chairs, sliding-door storage, and tables that could expand and contract as needed, or fold up to be put away completely. In her own home, metal storage units and wall-mounted shelving reduced clutter, and sleek sliding panels allowed the interior to transform from a place to host to a quiet zone. In her projects elsewhere, like the Maison du Mexique, a modular approach illustrated how this personal design could create affordable, efficient housing at a larger scale.

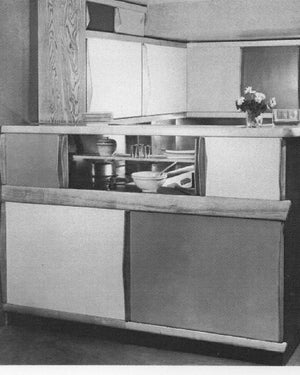

When Perriand began work in Le Corbusier’s studio, this included kitchen designs for Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, which included space-saving innovations that are common—though not always as thoughtfully considered—in contemporary architecture today. For Le Corbusier, considering small living spaces was an essential factor in the way he thought about city planning and architecture that might lead to a new way of living. In Marseille, Cité Radieuse and apartments in his Unité d'Habitation, design for each apartment was considered a “unit for modern living.” Their compact size meant that spatial efficiency was prioritized, in order to leave room for open and green spaces in spite of limited square footage. Multifunctional furniture (often by Perriand) was essential to bringing this to life.

Kitchen bar project by Charlotte Perriand for the l'Unité d'habitation, Marseille 194

© Le Corbusier: The Modulor (Book), 1950

Kitchen bar project for the l'Unité d'habitation, Marseille 1947

© Le Corbusier: The Modulor (Book), 1950

Cell 516, Le Corbusier Housing Unit, Marseille, 1952

©Laure Jegat

The salon of E 1027, the 1920s house on the French Riviera designed by Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici

© Alan IrvineWhether at Villa E-1027 or Tempe à Pailla, Eileen Gray’s designs are essential references to compact living—and how approaching this as a relationship between landscape, architecture, and interior design yields the most successful results. Considering how your furniture fits your space in particular—even if it isn’t custom designed as it was in Gray’s case—and how to let in light, air, and green space (whether through an open window, a house plant, or outdoor access) is a Gray-ism that remains an impactful approach in today’s apartment living. Gray designed built-in storage, folding furniture, and modular elements to maximize the space and create this visual and interior harmony—to maximize efficiency and comfort above all else.

The study area of the living room at Tempe à Pailla (1934) with a bar stool designed by Gray and a desk that could be folded up over the cork noticeboard on the wall

©National Museum of Ireland

The metal wardrobe hiding the sleeping area, with a perforated Plexiglass top, could be reduced or extended in size. Tempe à Pailla, Eileen Gray, 1934

©National Museum of Ireland

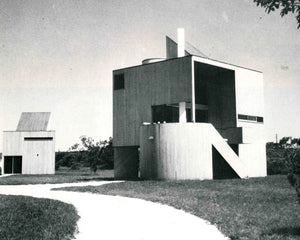

– Charles Gwathmey

At The Eames House in Los Angeles, also known as Case Study House No. 8, industrial, inexpensive materials created an adaptable layout that could be adjusted to suit specific needs day to day: from work studio to intimate space for leisure, to a space to host others and play. Designed in 1945, the house centered the comfort and needs of its inhabitants rather than a fixed layout. Twenty years later, architect Charles Gwathmey designed the Gwathmey Residence and Studio for his parents in 1965, located on a one-acre flat site on eastern Long Island that followed a similar approach, and led the architect to reflect: “I think constraints are very important. They’re positive, because they allow you to work off something.”

Gwathmey Residence and Studio Exterior, Charles Gwathmey, 1965

© Charles GwathmeyNow with the Compact Living collection, essentials for living in small spaces are recognized as the most imaginative design objects: paring furnishings down to their most important features, and leaving out the rest. By looking to architecture history, we can see that maximizing storage to minimize clutter is something that was on Le Corbusier and his contemporaries' minds as well, and that can lead to a living space pared down to its most comfortable, intelligent essentials.

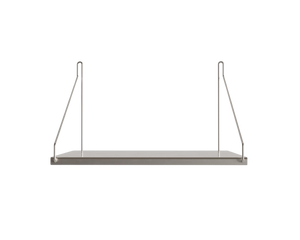

Single Shelf

Stainless Steel | D27 / W40

Farmhouse Coffee Table

Dark Oak | Pond

Petit Rond Stool

Stainless Steel

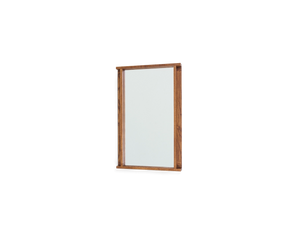

Symmetry Mirror

Honey Ash Wood | Small

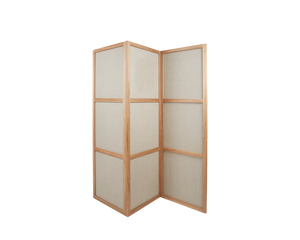

Frame Room Divider

Natural Oak / Linen | Three Panels

Easy Chair 01

Warm Brown Birch

Rivet Cart

Aluminum

KR180 Daybed

Light Natural

Adam Stool

Raw Steel / Natural Leather | H50

Folding Flat Trestle Table

Warm Brown Birch

Rivet Box Table

Aluminum

Folding Flat Chair

Warm Brown Birch

Scented Candle

1917 | 170 g

AML Stool

Pine

Wall Display

Stainless Steel | 375ml

Hand Wash

Apothecary | 375 mL

Farmhouse Trestle Table

Natural Oak | 120 Ø Round

Chair 01

Warm Brown Birch

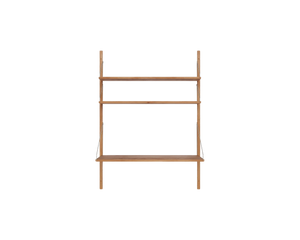

Shelf Library Desk Section

Natural Oak | H114.8 / W80